by Ed Simon

“But then again, what has the whale to say?” wondered Ishmael in Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby-Dick, “therefore the whale has no voice,” but this isn’t accurate. Sperm whales – of which Melville’s titular white whale is one – have an intricate series of clicks and bellows that if not language per se, certainly seem like communication, albeit in a manner foreign to human experience. Furthermore, not only do sperm whales, humpback whales, blue whales, dolphins and other members of the cetacean family make noise, they are capable of imitative sounds, of repeating complex strings of noises – songs and clicks of varying pitch and duration – back to each other. That’s an ability that, to varying degrees, is not just the purview of whales, but of seals and birds, bats and humans (but notably not some of our closest primate cousins, who though capable of understanding us are unable to vocally repeat what we’ve said). Now, a landmark study written by research teams at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of California at Berkely have been able to deploy complex machine learning technologies for the first time in untangling the genetic basis for language acquisition across tremendously varied types of animals.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Center at CMU doesn’t much feel like Ishmael’s ship The Pequod, but it turns out to be the perfect place to, if not discuss what the whale has to say, at least how the whale is saying it (and how bats, seals, and people are saying what they have to as well). Appearing more like a tech campus in Palo Alto than Pittsburgh, with an impressive central spiraling staircase whose shape is equal parts Frank Lloyd Wright and DNA’s double helix, the Gates Center is where I met team leader and professor of computational biology Dr. Andreas Pfenning who is the lead author on the study published in Science, the flagship journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Pfenning explained to me how beyond traditional anatomical and behavioral approaches, the CMU and Berkey study “opens up studying animal communication from a genetic perspective.” Read more »

.

.

Some things in life are very hard to give up. For me, I hope in a most singular manner, it is bullshit. I have spent nearly twenty years reading whatever literature I can find on what bullshit might be. Since the publication of Professor Harry Frankfurt’s

Some things in life are very hard to give up. For me, I hope in a most singular manner, it is bullshit. I have spent nearly twenty years reading whatever literature I can find on what bullshit might be. Since the publication of Professor Harry Frankfurt’s  In the late 1960’s and early 70’s, my maternal grandmother spent a lot of time in the United States. She would return to Iran, her suitcase filled with presents like candy and fruity bubble gum for her grandchildren, and pretty shirts and dresses for our mom. She also brought back a part of her daily American life: cartons of red Winston cigarettes, Crest toothpaste, hand and face creams with English writings on the bottles, and Dial Soap in that beautiful saffron gold color that was unlike any soap I had seen or smelled before. Our soaps in Iran were usually either flower scented and over perfumed, or green and organic because of the local olive oil used to make them. Everyone valued the green soaps, but I just wanted the American gold soap. I would watch her put the soap back in a plastic container after her shower to keep it from drying and when she was away from her room, I would go open the plastic container and smell the

In the late 1960’s and early 70’s, my maternal grandmother spent a lot of time in the United States. She would return to Iran, her suitcase filled with presents like candy and fruity bubble gum for her grandchildren, and pretty shirts and dresses for our mom. She also brought back a part of her daily American life: cartons of red Winston cigarettes, Crest toothpaste, hand and face creams with English writings on the bottles, and Dial Soap in that beautiful saffron gold color that was unlike any soap I had seen or smelled before. Our soaps in Iran were usually either flower scented and over perfumed, or green and organic because of the local olive oil used to make them. Everyone valued the green soaps, but I just wanted the American gold soap. I would watch her put the soap back in a plastic container after her shower to keep it from drying and when she was away from her room, I would go open the plastic container and smell the

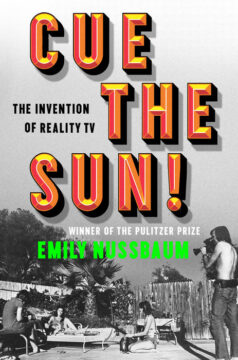

EMILY NUSSBAUM, THE PULITZER-WINNING television critic and New Yorker staff writer, ends her well-researched, somewhat grueling book on the history of reality television, Cue the Sun!, with a reminder that critics have historically dismissed reality TV as a fad. Yet reality TV has not gone away. It’s more than just a fad, she writes, because “in the end, all our faces got stuck that way.”

EMILY NUSSBAUM, THE PULITZER-WINNING television critic and New Yorker staff writer, ends her well-researched, somewhat grueling book on the history of reality television, Cue the Sun!, with a reminder that critics have historically dismissed reality TV as a fad. Yet reality TV has not gone away. It’s more than just a fad, she writes, because “in the end, all our faces got stuck that way.” In early May, Google announced it would be adding artificial intelligence to its search engine. When the new feature rolled out,

In early May, Google announced it would be adding artificial intelligence to its search engine. When the new feature rolled out,  In early 1824, 30 members of Vienna’s music community sent a letter to Ludwig van Beethoven

In early 1824, 30 members of Vienna’s music community sent a letter to Ludwig van Beethoven  F

F WHEN HAMAS TERRORISTS

WHEN HAMAS TERRORISTS